West Bengal’s Ghost Schools Crisis: 18,000 Teachers at 3,800 Schools with Zero Students

West Bengal’s “ghost schools” crisis: 18,000 teachers on payroll at 3,800 schools with zero students, nearly half of India’s total

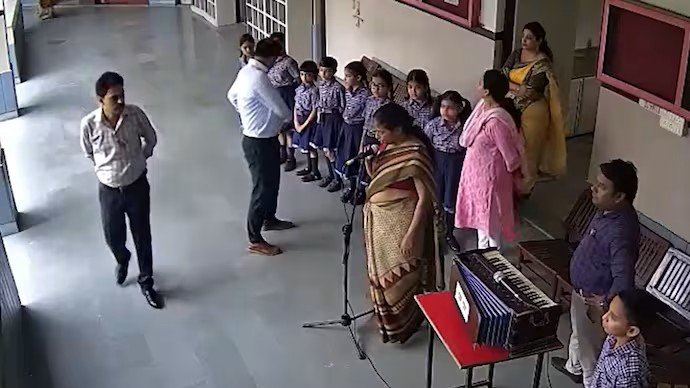

Fresh government data has thrown a harsh spotlight on West Bengal’s public-school system: the state has 3,812 government schools with zero enrolment, yet 17,965 teachers remain posted to these campuses. That means Bengal alone accounts for 47.7% of all zero-enrolment schools in India (7,993 nationwide) and 86.3% of the teachers employed in such schools (20,817 nationwide) in 2024-25—an extraordinary outlier that raises urgent questions about planning, oversight and accountability.

What the new data shows

The Union Education Ministry released the UDISE+ 2024–25 report in late August. At the all-India level, zero-enrolment schools fell from 12,954 (2023–24) to 7,993 (2024–25)—a 38% decline—and single-teacher schools also dipped to 1,04,125. But West Bengal moved in the opposite direction on the specific metric of “empty” schools, topping the national table with 3,812 such institutions and 17,965 teachers, far ahead of Telangana (2,245 schools; 1,016 teachers) and Madhya Pradesh (463; 223).

A detailed analysis based directly on the UDISE+ tables adds two striking contradictions: despite thousands of “ghost schools,” Bengal’s pupil-teacher ratio (PTR) is 29, worse than the national average of 24; and the state still runs 6,482 single-teacher schools with 2.35 lakh students (≈36 students per such school), indicating severe maldistribution of teachers.

How did we get here? Five structural fault lines

- Misallocation, not just shortage

Bengal’s higher-than-average PTR alongside teacher-heavy empty schools points to posting and transfer failures rather than a simple headcount problem. Students concentrate in a subset of schools while other campuses are left without children, yet remain staffed. - Parent flight to private/bilingual schools

Across states, families have moved towards English-medium or bilingual options, especially in urban belts. District-level reportage shows declining interest in government schools even where campuses exist—a pattern echoed nationally and in neighbouring states. - Urban concentration of zero-enrolment

Internal departmental tallies cited in July showed Kolkata alone accounted for over 34% of Bengal’s zero-enrolment schools—an urban paradox where schools exist but students do not, likely reflecting catchment changes and competition from private institutions. - Administrative churn & non-teaching burdens

Education-rights litigant argues the system has become a “rehabilitation centre for teachers,” overburdening them with non-academic tasks and enabling politically connected postings detached from student needs—conditions that allow zero-enrolment postings to persist. - Data improved, but the outlier remains

The centre’s dataset confirms national progress—fewer zero-enrolment and single-teacher schools overall—but Bengal’s share of the problem has grown more conspicuous, now hovering near half of India’s empty schools.

What the government says—and what it plans

The Education Ministry has advised states to merge or consolidate underused schools and rationalise staff. Some states have already linked recognition or funding to minimum enrolment; Uttar Pradesh plans to withdraw recognition after three years of zero admissions. West Bengal’s school board, for its part, has floated “cluster schools”—sharing teachers across nearby campuses—to plug subject-specific gaps without formal mergers. Whether that fixes empty campuses is unclear.

Why it matters

- Wasted public money: Paying nearly 18,000 teachers where no students exist is fiscally indefensible and diverts resources from overcrowded schools that need them.

- RTE compliance at risk: India still has over 1 lakh single-teacher schools—the Right to Education Act mandates one teacher per class, not per school. Persisting with empty schools while other campuses run with one teacher undermines the law’s spirit.

- Equity impact: Drop-offs and shifting enrolment hit poorer and marginalised communities hardest, especially where quality government options thin out and transport costs rise. Field reports from West Bengal’s districts have flagged these risks through 2025.

Countries with the Most Nobel Prizes 2025: U.S. Leads, India and China Rise in Global Rankings

What experts say should happen next

- Time-bound rationalisation of zero-enrolment schools (closure, merger or conversion to resource hubs), paired with transparent teacher redeployment to high-PTR campuses.

- Catchment mapping in cities like Kolkata to redraw boundaries and prevent multiple government schools from competing for the same shrinking pool of students.

- Parent-facing quality fixes—English/bilingual sections where feasible, predictable teacher availability, and visible learning guarantees—to stem flight to private schools.

- Independent audits of postings and attendance, with monthly public dashboards using UDISE+ fields (enrolment, PTR, teacher count).

The bottom line

UDISE+ 2024-25 confirms India is shrinking the number of “ghost schools.” West Bengal is the glaring exception: nearly half of the country’s empty campuses and over four-fifths of the teachers working in them are concentrated in a single state. Fixing this isn’t about more schemes on paper—it’s about moving teachers to where children actually are, consolidating campuses that have none, and rebuilding parent trust in government schools.

Sources: UDISE+ 2024–25 release and key tables

West Bengal ghost schools, zero enrolment schools India, West Bengal government schools crisis, 18000 teachers no students, UDISE+ 2025 report, education system failure West Bengal, empty schools in India, Indian education data, school enrolment West Bengal, teacher misallocation India

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 COMMENTS